An illustrative case of the pitfalls in assessing methodological quality is given by an interesting and recent review of all published epidemiological research looking at the neurodevelopmental effects of prenatal and postnatal exposure to organophosphate pesticides (González-Alzaga et al. 2013).

This study uses compliance with STROBE criteria, a checklist which has been developed to strengthen reporting standards in epidemiological research (STROBE 2013), as a way to score the methodological quality of each study in the review.

There are nine reporting requirements in STROBE which relate to methods used in an epidemiological study. González-Alzaga et al. calculate a score based on the number of criteria which are met by each study in their review, to give a score out of 9. This is then simplified to a quality grade of low (meeting 1-3 criteria) medium (4-6 criteria) and high (7-9 criteria) for each study.

The first problem with this approach is it conflates the quality of reporting a study with quality of conduct of a study. Since what was said was done in a study may not reflect what was actually done, simply relying on what study authors report can lead to over- or underestimation of the quality of a piece of research.

Much more interesting, however, is in the use of STROBE as a quality scale. This gets to the heart of what quality appraisal is all about, and why it is so challenging.

What is the point of assessing the methodological quality of a study? To get a sense of whether or not we can believe its results, in other words the probability and extent to which it might have under- or overestimated effect size. So our metric for study quality should address precisely this.

The problem for González-Alzaga et al. is they have assumed that each STROBE criterion counts equally towards the overall credibility of a study. But why should this be the case? It is a stretch to assume that a failure to present key elements of study design early in a paper (one of the STROBE criteria) should count as much against a study as a failure to explain how loss to follow-up of cohort members was addressed (another of the criteria). [A full list of the criteria can be downloaded from the STROBE website, here.]

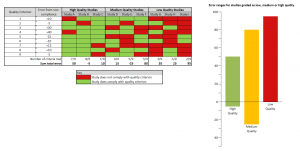

If we assume each quality criterion in fact has a different effect on study credibility, we can see how a checklist can fall apart as a proxy for measuring study quality (see figure, above).

Here we see that for a group of nine studies, three for each quality category, variance in study error is not correlated with the judgment of study quality: the high-quality category contains a study with a greater degree of error than two of the studies judged to be of lowest quality; and one of the medium-quality studies has the second-highest error margin.

To make it work as a checklist, the overall error which failure to meet each STROBE criterion introduces into a study would have to be measured. The temptation to combine criteria into a single judgement would have to be resisted, as it can easily result in studies judged to be of overall higher quality in fact giving worse results than studies judged to be of lower quality. It would also be important to make sure the STROBE criteria did not miss anything which can introduce error into a study’s results.